Following on from Ireland’s slave-owning past, and present (part 1), in this post I want to profile the walking tour I led in Dublin city in early February. This tour was kindly sponsored by the Young Irish Georgians who covered the public liability insurance for this tour. I did not take a fee for delivering this tour. All proceeds will be donated to Movement of Asylum Seekers in Ireland (MASI).

I want to start this post by again highlighting the stellar work of Dr. Ciaran O’Neill who is a leading researcher into Ireland’s slave-owning histories. His 2022 lecture, The Public History of Slavery in Dublin is an essential read for anyone interested in learning more about slavery as it relates to Ireland. Ciaran has been extremely generous with his time, and I’m grateful to him for conversations and emails exchanged.

And just a FYI for Dublin-based folks, Ciaran O’Neill will be taking part in the Trinity Talks series on 27 May and you can register for his discussion on Dublin’s Slavery Mansions here.

Finally, this walking tour was devised using information taken directly from the Legacies of British Slavery database. Truly, one of the most important pieces of research out there - and fully accessible to all.

How can we trace Dublin’s slave-owning past?

In Ireland, in February, when leading a walking tour - you hope against hope for a dry day. Setting off from Mountjoy Square with greys upon greys, the sky held strong for us fifteen people as we embarked on two hours of learning about Dublin’s slave-owning histories.

In the eighteenth-century, Dublin was one of the largest cities in the British Empire, with a population of approximately 65,000 in 1700.1 In the one-hundred years between this date and the 1800 Act of Union - which saw parliamentary business relocating to Westminster following the 1798 rebellion by the United Irishmen - Dublin flourished as a colonial city. And as a colonial city, many Dubliners participated enthusiastically in slave ownership in the Caribbean until its abolition in 1807 (please note: this blog pertains to Irish slave-owners in the Caribbean only).

It might be strange to think of Dublin as a “colonial city”. In 2025, Dublin sees itself as a dynamic modern and European city, progressive and a proud Republic. Ninety miles up the road in Belfast, the difference is stark. The echoes of Queen Victoria, the World Wars, shipbuilding and ornate British architecture define that hardened city - whereas Dublin has a softness, an “Irishness”, to it. Perhaps this softness is explainable by the removal of the architectural remnants of Empire, no more clearly seen than in the blowing up of Nelson’s Pillar in 1966 by Irish Republicans.

If we are to imagine Dublin as a colonial city, and its occupants participating in the spoils of Empire, we have to live in a liminal space for a moment. What is not said, what is no longer present; these historic vibrations are what we must lean into when undertaking this tour.

Dublin’s outward face has changed but the fingerprints of collaboration endure.

Gradients of participation in slave-owning

The British Parliament abolished slavery in the Caribbean, Mauritius and the Cape in 1807 - but the implementation of abolition was an incredibly slow-moving process, taking another 26 years from 1807 to effect the emancipation of the enslaved in 1833. Indeed, even after 1833, while most enslaved persons in the Caribbean were “freed” - many were forced into “apprenticeships” (akin to the indentured servitude experienced by some white Irish) where they were tied into unfree labour for fixed terms.

For slave-owners affected, abolition signified in their view, a loss of “property” and money. To placate these slave-owners, the British Treasury committed to paying financial “reparations” (please read part 1 to explain why I am using this term) as a form of compensation. As a result, hundreds of persons in Britain submitted applications for “reparations”. Thanks to the research work carried out by the Legacies of British Slavery project, what we can view now in 2025 are detailed records and paperwork that many slave-owners used in their applications.

The above image is an example of the documents that enable us to establish a paper trail showing how slave-owners applied for reparations. The image provides a list of enslaved persons and how they were categorized, listed and priced in terms of “value”. The title reads: “A descriptive list of Negro and other slaved belongings”. Column headings appear to say: “No” (Number), “Name”, “Supposed Age”, “Employment”, “Condition”, “Value”. At the bottom of the list, the “value” of these persons is calculated.

For reference: £8,705 in 1833 is worth about £1,325,000 in British pounds today.

These documents allow us to map not only those explicitly involved in slave-ownership, but as we will find out, they help to identify persons attempting to extract money from the British Treasury through tangential associations with slavery. These gradients of participation in slave-owning will paint a picture of the ownership of human beings as an entirely acceptable endeavour in Ireland.

The presence of slave-ownership in Dublin

Using the research from the Legacies of British Slavery database, I constructed a walking tour to profile some of the homes, businesses and landmarks in Dublin that demonstrate activity in slave-ownership. To give a sense of the numbers of those who participated in slave-ownership, the database itself holds 4,000+ estates and identifies over 20,000 slave-owners in Britain.

My walking tour profiles a few examples of Dubliners involved in the slave-trade and certainly other walking tours could be devised using a variety of different locations. For the purpose of this blog, I will only profile the sites visited as part of my tour. Here is a link to a Google Map highlighting each stop.

Our tour began at Mountjoy Square, Dublin - one of the most famous Georgian Squares in the city. Developed by the 1st Viscount Mountjoy, Luka Gardiner, construction for the square began in the 1790s and was completed in 1818. Terraced Georgian houses built in distinctive red brick surround all sides of Mountjoy Square.2 An enviable location for the upper class Dubliners, Mountjoy Square was populated by the good and the great of Irish society. And with that in mind, this square brings us to our first slave-owner, Dr. Thomas Neilson.3

Dr. Thomas Neilson, Mountjoy Square

As a Tyrone girl, it felt only right that my first stop on this slave-owner tour should have links to my own native county. From Mountjoy Square to Mountfield, no region of Ireland - whether urban or rural - is untouched by the poison of slave-ownership.

In this case, we can stop and take a look at the Neilson family who hailed from Strabane, Co. Tyrone. Likely coming to Ireland during the period of the Plantation of Ulster (1609), the Neilson family lived on land owned by the Earl of Abercorn. Today it’s possible to visit Baronscourt, the home of the Abercorns, in Newtownstewart, Co. Tyrone.

In 1790, we can see evidence of William Neilson signing a letter of gratitude to the Earl of Abercorn, praising his donation to “our fund established for the relief of the poor”.4 What we can perhaps discern from this association with aid for the poor is that the Neilsons were civic-minded, Christian folks with enough prosperity to do aid work, rather than require it.

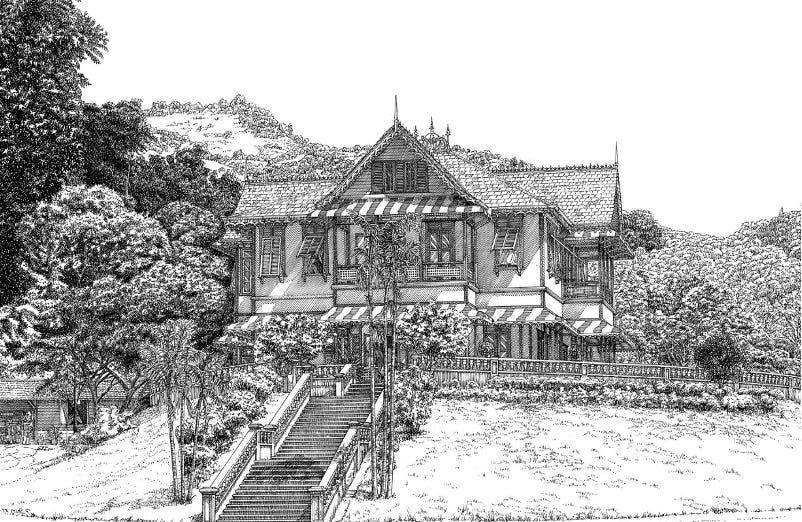

William Neilson’s son Thomas was the family’s first foray into slave-owning. Born in 1798, Neilson travelled to Trinidad and made his living as a slave and plantation owner. His estate home may have looked like the below:

Following the abolition of slavery in the Caribbean, Dr. Thomas Neilson made the following claim for reparations:

Trinidad (plantations unknown):

25 enslaved persons valued at £1422 (£207,500 in 2025)

90 enslaved persons valued at £4267 (£622,800 in 2025)St John Estate, Trinidad:

44 enslaved persons valued at £2322 (339,000 in 2025)La Perseverance Estate, Trinidad:

64 enslaved persons valued at £3354 (£489,500 in 2025)

Neilson’s fortunes were made through his ownership of people in the Caribbean. Later in life, he returned to Ireland, residing in Mountjoy Square with his wife Eliza. He died in his Mountjoy residence in 1866, aged 77.

Dr. Thomas Neilson is a typical and outright example of slave-owners from Ireland. We can clearly see his participation in slavery through his movements and reparation requests. What I find illuminating and insidious, however, is what happened after his death in 1866.

Thomas Neilson Underwood and the contested will

Following Dr. Thomas Neilson’s death, his will was successfully contested by his nephew, Thomas Neilson Underwood (I will call him “Underwood” from now on). Underwood was a significant figure in Irish life, so much so he has his own listing in the Dictionary of Irish Biography (DIB).

From this entry, we can discern that Underwood was the son of Dr. Thomas Neilson’s sister Margaret, and like his uncle, was probably born in Strabane, Co. Tyrone. Underwood was a Presbyterian solicitor and identified as an Irish Nationalist, founding the National Brotherhood of St. Patrick in 1861. This Brotherhood flourished particularly in Fenian diaspora communities in England in the 1860s. By the time it lost its popularity, Underwood too had stepped back from the Brotherhood - but remained a trusted ally of the Fenians.

Underwood’s successful contesting of Dr. Thomas Neilson’s will meant that he inherited money directly made from the profits of slave-ownership.

At this point I will divert briefly to mention that the DIB notes Underwood’s maternal grandfather William Neilson was a 1798 sympathiser. This correlates with his advocacy for the poor, as demonstrated in the letter signed by the Earl of Abercorn I mentioned earlier. The DIB entry also states William Neilson was “allied by consanguinity” with Samuel Neilson, a key link between the Dublin and Belfast United Irishmen. So too, Samuel Neilson was a friend and comrade of Henry Joy McCracken who along with his sister Mary Ann McCracken were committed abolitionists. One would wonder how William Neilson may have felt about his son profiting from slave-ownership considering his allyship with Samuel and proximity to the McCrackens?

One might also wonder how Underwood, whose principles and morals seem aligned with the principles of liberte, fraternite and egalite could contest the will of Dr. Thomas Neilson knowing that this money came directly from slave-owning?

To make matters even more sickening, we know that after his successful contesting of Dr. Thomas Neilson’s will, Underwood continued to participate in a range of political activities in Ireland, including attending the raising of the last stone of the first memorial to Daniel O’Connell, erected in Ennis, Co. Clare in 1867.

Here is a report from a speech given by Michael G. Considine prior to the launching ceremony:

“Don't think it was to ornament our town that I laboured; no, nor to honour the mighty dead as the emancipator only; no, but as the Repealer also; and give three cheers for the repeal of that base Act of Union. Oh! may your voices reach to the throne of heaven, to bring down a blessing on your honest intentions towards your suffering country. May it reach across the Atlantic and every other part of the earth where an Irishman is found. May it arouse them to a sense of their duty towards poor Erin. The Irish abroad do not forget faith and fatherland.”

After several other remarks, the speaker concluded by passing the vote of thanks, and said he hoped the statue would be soon done, when they would hear on the day of the inauguration such Irishmen as Father Vaughan, Father Lavelle, The O'Donoghue, Thomas Neilson Underwood, and other good and true Irishmen; that he would then wear the suit of green he was presented with by the Nationalists and Irishmen of London.5

To my mind, this report demonstrates a few things. Firstly, that Underwood was invited to the launch of a statue of Daniel O’Connell, the Great Emancipator and abolitionist who met with Frederick Douglass and implored the Irish diaspora in the United States to have nothing to do with, and to oppose the monstrosity that is slavery, is laughable. How did Underwood pay for his train ticket to Ennis, for the clothes he was wearing, the food he ate en route? How did Underwood occupy financial privilege enabling him to be an intellectual and to be politically minded? His uncle’s slave-owning money of course.

Secondly, the thread of white Irish exceptionalism that I explored a little in part 1 of this blog is particularly evident here. Considine’s words about “poor Erin” and attempts to reach the diaspora using a narrative framed by oppression and the seeking of liberation could easily be transplanted into the rhetoric of white Irish migrants today who sought a better life in the United States and promptly closed the door of opportunity behind them. A surprisingly excellent recent article from BBCNI probes this very well.

With one hand, white Irish in Ireland erect statues to abolitionists and lament our oppressions; and with the other, they invite speakers whose livelihood is derived explicitly from the profits of slave-ownership. If that doesn’t sum up the insidious nature of how slave-ownership infects Ireland, and the narratives about us that we tell ourselves, I’m not sure what does.

Wherever slavery rears its head, I am the enemy of the system

I am going to end this post now and write a part 3 that looks at the rest of the stops in my walking tour in more detail.

It was important for me to unpack this first stop because of the complicated legacy of Dr. Thomas Neilson’s money. I also think the intertwining of this family with 1798 thinkers, Fenians and Irish Nationalism as well as with Daniel O’Connell illustrates how slave-ownership was so sanitised in some quarters that it was not incredulous to marry it with progressive, anti-colonial and enlightened thinking. Underwood demonstrates how one can be an admirer of O’Connell and simultaneously profiting from slave-ownership.

To finish, I think it’s apposite to include a few words from O’Connell who surely would have cast out a figure such as Underwood, should their paths have ever crossed. One would think too, with the current genocide being committed in Gaza and the havoc being wreaked by the fascist Trump administration, our own Irish and Northern Irish politicians could take a leaf out of O’Connell’s book and stand with those oppressed, and to hell with the consequences.

“I do not hesitate to declare my opinions. I never faltered in my own sentiments. We might have shrunk from the question of American slavery, but I would consider such a course unworthy of me. We may not get money from America after this declaration; but we do not want blood-stained money. Those who commit, and those who countenance the crime of slavery, I regard as the enemies of Ireland, and I desire to have no sympathy or support from them. I am not bound to look to consequences, but to justice and humanity. Wherever slavery rears its head, I am the enemy of the system.”6

— Daniel O’Connell speech delivered at a Dublin Anti-Slavery Society meeting, 1830.

Dublin Civic Trust (2024) The development of Dublin. Available at: https://www.dublincivictrust.ie/dublins-buildings/development-of-dublin- (Accessed: 02 April 2025).

For more information about the history of Mountjoy Square, see: https://mountjoysq.com/

Thanks are owed to

and his excellent Substack which informed so much of my research here.Ulster Ancestry (2019) We, the inhabitants of Strabane. Available at: http://www.ulsterancestry.com/free/ShowFreePage-464.html#gsc.tab=0 (Accessed: 02 April 2025).

Clare Libraries. (2019) Michael G Considine and Daniel O’Connell. https://clarelibraries.ie/localstudies/clare-past-forum/viewtopic.php?t=6831&start=15 (Accessed 01 April 2025).

O'Connell, D. & African American Pamphlet Collection. (1860) Daniel O'Connell upon American slavery: with other Irish testimonies. New York: Published by the American Anti-Slavery Society. [Pdf] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/92838911/.

What if some of those who inherited slavery tainted funds paid their own reparations to the people their relative “owned” before embarking on an antislavery campaign of their own. Would this have been enough to wipe away the taint of a family having owned slaves? To never have contemplated owning another person or selling them into servitude would be the ideal. But once such and act is countenanced, what then for the generations that follow?

Thanks for your shout out, Maeve! I read with dismay the article you linked to about Irish Americans "jumping on the Trump train." This is a shameful chapter for my country, and I hate to think of anyone in Ireland imagining that descendants of those who emigrated to the US are especially vulnerable to his call to greed and spite. Your reflections on Thomas Neilson and his nephew Thomas Neilson Underwood open up an interesting area of inquiry. Thomas Neilson Underwood does seem to have made the claim that his grandfather William was a United Irishman and a relative and sometime-abettor of Samuel Neilson. If the connection between William Neilson and Samuel Neilson did exist in the late 18th century, then William's family in Strabane would have been aware of Samuel hosting Olaudah Equiano who was on an abolitionist speaking tour in May 1791, just a few months before the founding of the UI. Thomas would have been a toddler at the time, but his brother Robert--who also went to Trinidad and made a fortune in the slave-based economy--would have been ten. Some skepticism is warranted, though. TNU was an unreliable narrator: the case of Thomas Neilson's disputed will turned partly on a forged document TNU produced and at least some of his jail time appears not to have been for his Fenian activities, but instead for malfeasance in his work as a solicitor. But if Thomas and Robert Neilson truly were exposed to cogent moral arguments against slavery *before* they embarked for the sugar islands, that makes their story all the more complex and, frankly, ugly.