Sylvia Plath, I'm now ten years older than you

Will the hive survive, will the gladiolas / Succeed in banking their fires / To enter another year?

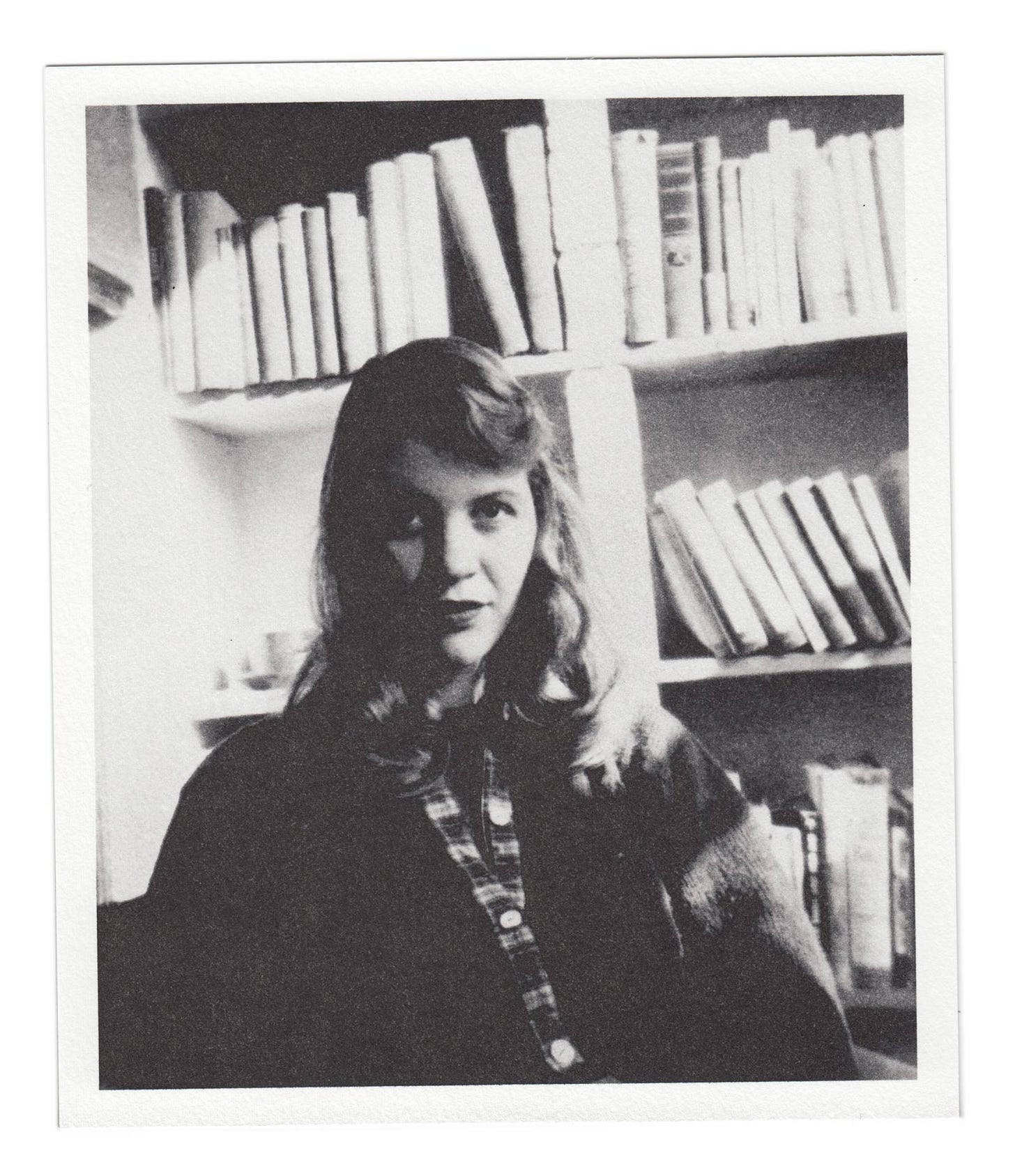

I became ten years older than Sylvia Plath yesterday. Make of that calculation what you will! Although Plath now takes up a sizably less presence in my brain, there are always traces of her speaking to me. I imagine and hope that will continue throughout the rest of my life - which already stretches out far beyond her young years. In all, I spent six heavy years researching her work - a collection of writings that is so enmeshed with her personal life, it does at times feel as though I walked in her shoes. Sylvia Plath is one of my great loves.

Once, in a devastating e-mail I received from another great love, I was told that I had spent too long in Plath’s head to ever trust the world and the people in it. For a while, I wondered if this was true. Most of us humans look to those who have come before us for inspiration, for instruction on how to “do life.” As a woman in the world, the lessons Plath’s life and work have taught me range from working hard to seeking adventure. To feeling and loving and succeeding and failing. And, yes I suppose - to be wary of the pitfalls of giving all of yourself away to others.

Plath was and is, many things to many people. A cypher with which so many of us glass-half-empty girlies project ourselves onto. An ambitious, powerful, intelligent woman derailed by the love of a, frankly, bad man. She was naive, she was fierce. She was one hell of a writer. Plath was a daughter, a mother, a sister. She was quite conservative. She enjoyed the privileges of whiteness. She wasn’t really a girl’s girl. She was only just getting started when she took her life by her own hand - alone with two small children under three - in London, in the dark winter of February 1963.

Writing a PhD on Sylvia Plath took up the bulk of my thirties. The opportunities and gifts I received from this process are immeasurable. I spent a semester at Smith College, visited Indiana University in Bloomington (and touched her hair). I had the opportunity to travel to conferences, meet likeminded people, and ultimately the career and life I have today is down to that PhD and Plath’s enduring presence as a force in my mind telling me to never ever give up, the only person you truly have is yourself and do not fuck this up because it’s your only chance to make something of yourself.

In the height of dissertation stress, I would dream of Plath. I dreamt of her at a party - being awful to everyone - she came over to me and put her hand on my chest and told me it’s time to wake up.

How much of that was real is anyone’s guess, really. The mind goes to funny places when you’re in the final weeks and months of writing a thesis. Even if it’s just her image as a cypher, Plath taught me a lot: the value of work, to be always aware of the smog of hell of domesticity, and the capacity of heterosexual relationships to ruin women. I learned about literary snobs, I learned that people in academia are mostly bluffing about their intellect. I learned that despite doubting myself every step of the way, there is nevertheless a rock hard part of me that believed in myself and in my calling to write. My calling as a writer? I call that part of me Sylvia.

I came to the day with acceptance. My fortieth birthday. Last year, the idea of youth slipping through my fingers upset me - despite being an awkward teenager, an out of control 20-something partygirl, and experiencing a chaotic and punitive thirties. Good therapy helped. Surrounding myself with my community of chosen family helps. That part of me that believes in myself (Sylvia), that helps too.

The phase of Plath’s life that I tend to think of most now is her time in Devon. I’ve written academic chapters on this time in her life. Here, she lived in the huge old house, Court Green (mortgage deposit paid for by her mother), and attempted to have the life that she and her husband had dreamed of. They hoped to be self-sufficient, away from literary snobs and cliques, to live and write and have children and be in love, and be everything to each other. Did it even last a year before her husband philandered? Sylvia Plath, the genius, the spoiled brat, the over-achiever, the brilliant! Her husband humiliated her, isolated her and abandoned her. She was left thousands of miles away from her friends and home.

It was easy for the male English poets sniggering at Plath to say she was “too much” - they all labelled her “gauche.” The moment her husband abandoned her, literary circles turned on her. I take great satisfaction knowing that Plath’s literary legacy has and will outlast them all. Having disposed of her in 1962, Plath’s husband wrote poems about her decades after her unnecessary death, poems about scissors being lost in the garden when Plath went out to pick daffodils.

Finally, we were overwhelmed

And we lost our wedding-present scissors.Every March since they have lifted again

Out of the same bulbs, the same

Baby-cries from the thaw,

Ballerinas too early for music, shiverers

In the draughty wings of the year.

On that same groundswell of memory, fluttering

They return to forget you stooping there

Behind the rainy curtains of a dark April,

Snipping their stems.But somewhere your scissors remember. Wherever they are.

Here somewhere, blades wide open,

April by April

Sinking deeper

Through the sod – an anchor, a cross of rust.- Ted Hughes, ‘Daffodils’.

One wonders if even a small amount of this tenderness or care had have been extended to Plath in the winter of 1963, would she still be here writing - as a Grand Dame of literature? But really, Birthday Letters are poems that lack depth from a husband who situates himself as a bystander in his own life. Despite the mourning tone of this poem, Ted Hughes’s low-key shaming of Plath for wanting to sell their daffodils for money speaks to the superiority of the English “art for art’s sake” attitude, and how he perceived Plath’s betrayal of this through her hyper-capitalist American view on making bank from the written word.

Really, by the 1990s, Plath became a cypher for Hughes, too.

I visited Court Green back in 2013. I expected it to be an idyll and that I would feel Plath’s power running through my veins as I stood there looking at it. Here, at that window on the right of that photograph, Plath wrote the guiding words of so many of us: ‘Lady Lazarus’, ‘Daddy’, ‘The Moon and the Yew Tree’, ‘Berck-Plage’. Here, she was one of the first poets to take objects of domesticity, account for them and transform them into poetry.

In Plath’s world, plates and mugs form foundational elements of Epic poems. Cutting onions became a monumental moment that demanded poeticisation. The image of a woman using her body to dry plates with her hair, witnessing her individualities and strangenesses evaporate serve so viscerally as a precursor to the frustrations and rage of the second-wave feminist movement that would follow months after her death:

I am no drudge

Though for years I have eaten dust

And dried plates with my dense hair.

And seen my strangeness evaporate,

Blue dew from dangerous skin.- Sylvia Plath, ‘Stings’.

My take-home from visiting North Tawton was that Court Green was a big, dark, empty and lonely house. In the 1960s, I can only imagine the number of rats running in the thatch. The village of North Tawton was parochial - even in 2013. Plath would have been a total outsider here, an American in rural England.

Dampness in the bones. Loneliness. Many of the villagers thought Plath was her husband’s mistress because she used her maiden name for correspondence. Two children to care for. A husband flirting with a local teenage girl right under her nose. A husband inviting his affair partner to their home, their safe space.

When I started my PhD, so much of the critical work on Plath (and Hughes) was written fuelled by internalised misogyny (Anne Stevenson / Olwyn Hughes) or by men like Jonathan Bate who made sure to report that once during a telephone call, Plath covered her naked husband’s phallus with her foot, to preserve his dignity. It still takes my breath away that someone actually fetishised Plath so blatantly and swarmily in what passes for “literary biography.”

But what of Plath’s dignity? And as I project myself onto her, I wonder am I absorbing her in the same way these literary bros have done? All I know is I’ve walked a little in her shoes and seen the realities and practicalities of her life. I’ve stood at the doorstep of that awful flat on Fitzroy in London - the one she poeticised in ‘Snow Blitz’ - and the one she died in. I’ve mourned the loss to literature from her death. The loss of Plath and the loss of the many thousands of women whose voices were extinguished by men, patriarchy and barriers of race, class and the domination of literature by the western canon.

Now that I’m entering a new decade, like Plath in ‘Daddy’, I’m through with all the trappings of the past. Of not being seen in the way I need to be seen. Of being afraid to put pen to paper and writing, despite my brain and fingertips starting and abandoning draft after draft of “my novel.”

I think of women from previous generations, like Plath. Like my grandmother who turned 40 in 1964, widowed with five children (and one dead) with the Troubles about to stretch out in front of them all. My own mother at 40, prioritizing the education of her children above everything else. That prioritization allowed me to be the first person in our family to go to University.

Like Plath, I’ve spent my youth struggling and fighting and trying to put pen to paper and be heard, be seen. But we’ll never know how Sylvia Plath would have lived the rest of her life. If she would have moved back to America after that winter of ‘63, if she would have become a feminist leader, if she would have called it a day for writing and trying and just went away with her children to a safe and loving cocoon? The type she wrote about in the autumn of 1962:

Love, love,

I have hung our cave with roses,

With soft rugs—

The last of Victoriana.

Let the stars

Plummet to their dark address,

Let the mercuric

Atoms that cripple drip

Into the terrible well,

You are the one

Solid the spaces lean on, envious.

You are the baby in the barn.- Sylvia Plath, ‘Nick and the Candlestick.’

I don’t know what will happen in this next decade for me. I have optimism though that it’s going to be good. I’m going to remain curious and open. I’m going to approach interpersonal relationships with the learnings and baggage and issues I have - but also the joyful playful honesty that makes up my personality.

If a person decides to tell me that spending time with Plath has made me incompatible with the world and mistrusting - I will re-evaluate my relationship with that person. How could I abandon the woman who in ‘Wintering’, asked this question of her bees and bee-keeping: “Will the hive survive, will the gladiolas / Succeed in banking their fires / To enter another year? What will they taste of, the Christmas roses? / The bees are flying. They taste the spring.”

With ‘Wintering’, Plath provides her last page of the blueprint - will I survive? Will I survive another year? As a March baby, writing this with the sunlight streaming in the window of my apartment, I can tell you now, I do taste the spring. And it’s freedom.

Just a brilliant insightful read

If this was a book, I'd be so excited to read it! Happy Birthday Maeve. Thanks for sharing this beautiful piece with us 💕