The Unbearable Whiteness of the Beat Generation

Unpacking cultural appropriation, patriarchy and the muted critical analysis of racism in Beat Generation poetry and fiction

For a few years, my teaching workload at a small university in Ireland included a module option on mid-century American literature. Coming off the back of a PhD on Sylvia Plath, and with the passion and enthusiasm of someone who hadn’t yet been ground down by the wheels of academia, I was handed a series of interesting classes but identified they were in need of some serious diversification.

It was important to me that students who took my classes understood the overall context of the predominately white poetic movements they were being taught. To my mind, nowhere was this recalibration more urgent than relating to how the “Beat Generation” writers were being taught - and understood by students.

Teaching Beat Poetry attracts students who often identify themselves with the writers and characters of novels that burn and blaze so bright for such short a time. As a young student myself back in the 00s, I was always partial to a rolled-up cigarette and playing a YouTube recording of Ginsberg at 3am at a house party.

So, when I embarked on teaching the Beat Generation writers, it was important that I gave a rounded perspective on their contributions, flaws and appropriations.

Down and out, but full of intense conviction

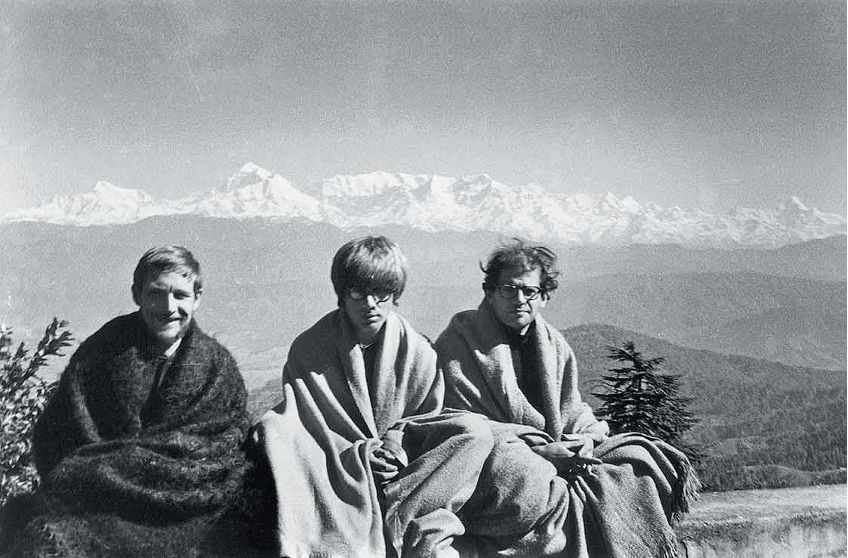

As a subculture (not counter-culture),1 the Beat Generation rejected the conformist, consumerist society of America in the post-war 1940s - but they did not go so far as to rebel against it. Indeed, for east coast Beats like college dropout Jack Kerouac, “hobos” like Herbert Huncke, and vagabonds like Neal Cassady - the goal was to be, “a generation of crazy, illuminated hipsters, suddenly rising, roaming America, serious, curious, bumming and hitchhiking everywhere, ragged, beatific, beautiful in an ugly, graceful new way”.2 These writers converged on New York, hanging out in places like Tompkins Square Park - bringing performance to their poetries, but not seeking to make meaningful societal change.

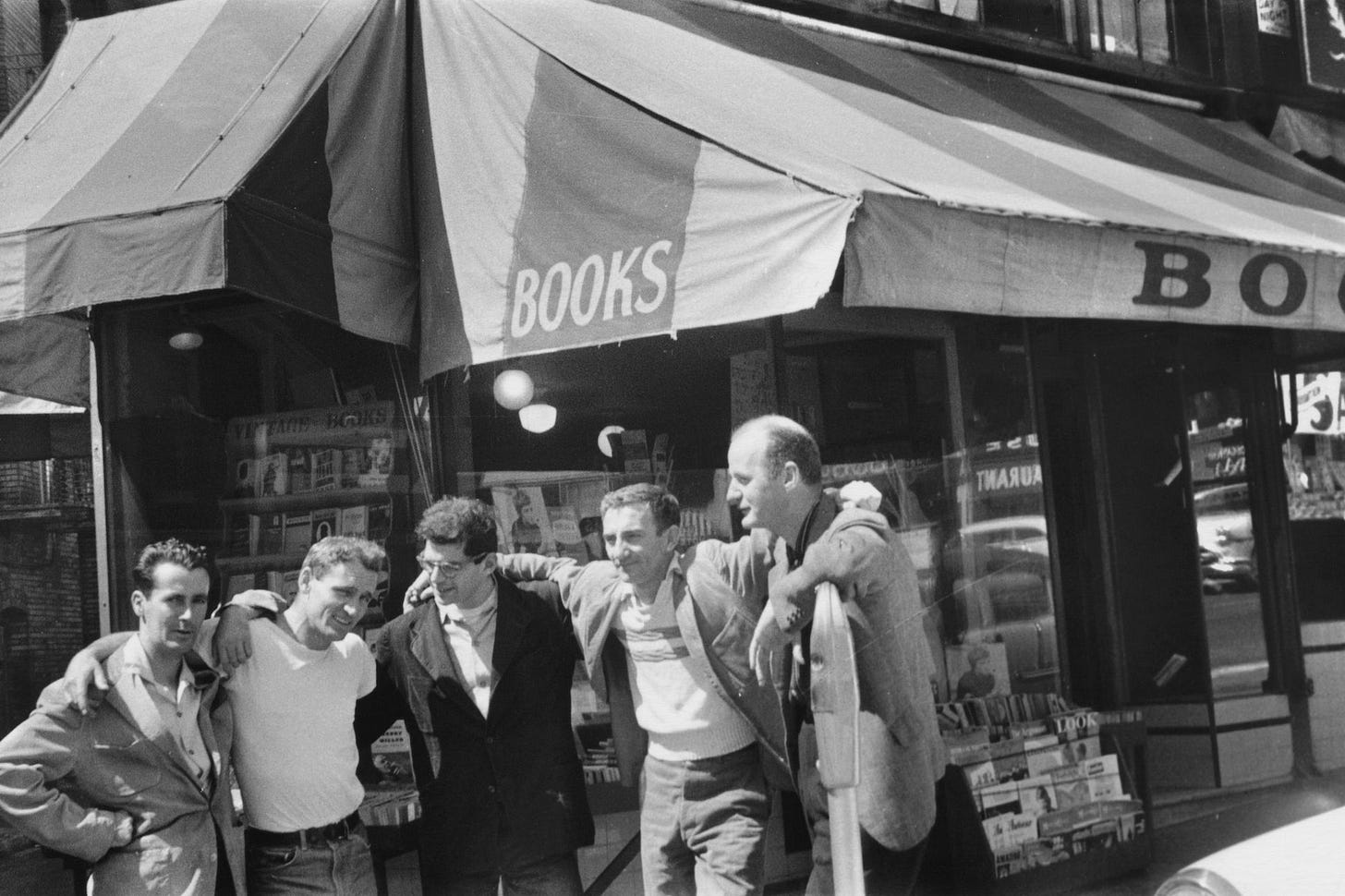

For west coast Beats, however, the goal was slightly different. San Francisco’s City Lights Bookshop (still open today) was the meeting place for experimental Beat writers like Allen Ginsberg, Lawrence Ferlinghetti and Gary Snyder; and “Beat” took on spiritual connotations - using literature and lived experience to achieve a higher understanding and consciousness of self.

Like their east coast counterparts however, the west coast Beats largely looked inner and indulged in individualistic desires, rather than engaging with problems or injustices in contemporary society.3

But why am I spending time chastising the Beats for their lack of engagement in social and cultural change? Do artists need to respond to the world they live in just because they are artists?

My answer is two-pronged: firstly, being “apolitical” is a political stance. No matter your interest, position or place - we all live in a politicised and unequal world. If you possess the privilege that allows you to ignore societal issues (until the issues come knocking on your door), it doesn’t mean you’re absolved. Secondly, because of their cultural currency - and the many young writers influenced by their words even to this day, there is the temptation to give the Beats a well-meaning pass in lieu of the inspiration they created. But unfortunately, for me, that cannot hold.

Who took the picture of you three?

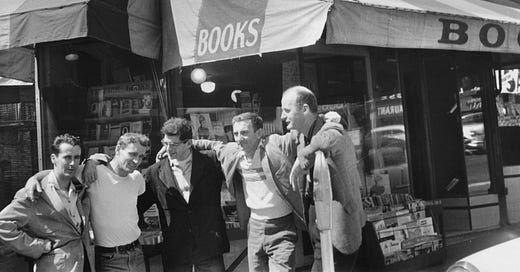

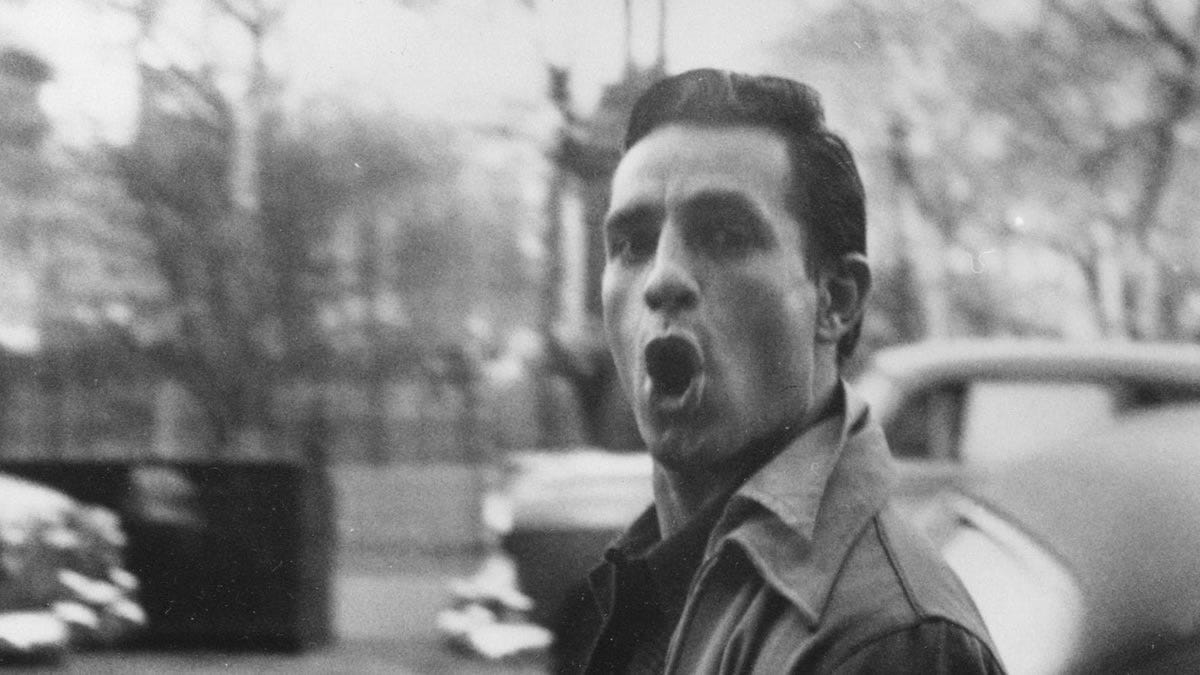

Like most principally white male literary groups of the twentieth-century, hierarchies of discrimination are apparent with just the smallest scratch under the surface of the Beat Generation. Take for example, the image below:4

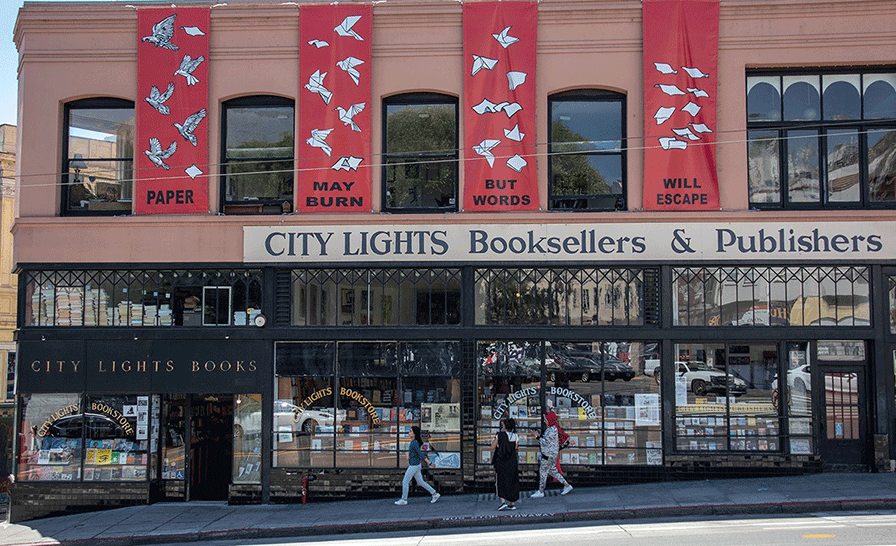

Nearly thirty-five years later, in the poem “Poison Oak for Allen”, Joanne Kyger wrote:

Here I am reading about your trip to India again,

with Gary Snyder and Peter Orlovsky. Period.

Who took the picture of you three

With smart Himalayan backdrop

The bear?

Writing to a 1990s audience, Kyger asks the reader to look beyond the foreground of this photograph and to consider the picture-taker. Having been written out of her place in the trip to India she shared with Ginsberg, Orlovsky and Snyder, Kyger re-inserts herself with this poem. (I have similar thoughts about this photo, taken at a Faber & Faber party in London in 1960 - Sylvia Plath was also in attendance and exists somewhere behind the photograph-taker).

More damning words regarding the position of women within the Beat Generation are found in Anne Waldman’s Women of the Beat Generation memoir and oral history collection:5

“I knew interesting creative women who became junkies for their boyfriends, who stole for their boyfriends, who concealed their poetry and artistic aspirations, who slept around to be popular, who had serious eating disorders, who concealed their unwanted pregnancies raising money for abortions on their own or who put the child up for adoption. Who never felt they owned or could appreciate their own bodies. I knew women living secret or double lives because love and sexual desire for another woman was anathema. I knew women in daily therapy because their fathers had abused them, or women who got sent away to mental hospitals or special schools because they’d taken a black lover. Some ran away from home. Some committed suicide. There were casualties among the men as well, but not, in my experience, as legion.”

Waldman, again writing retrospectively (notice a pattern here? Where Beat women didn’t write as much as their male counterparts during the 1940-60s and instead carved time in the years afterwards?) offers an eviscerating assessment of the position of women in the Beat Generation, describing how “dropping out” had dire consequences for women at a rate much more insistent than for Beat men.

And while it must be said that other women Beats such as Diane DiPrima spoke effusively about being mentored by Ginsberg, and having Kerouac “re-write” her diary entries for her - as a prefigurement to Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique (1963) and even Mulvey’s “male gaze” (1973), Waldman’s summary of women’s lived experiences alongside the Beat men tracks.

“Let the world be a black poem”

By and large, I have been talking about a lot of white folks so far here. White men dropping out and writing about it. White women dropping out, trying to write and trying to exist under the micro-patriarchy of the Beat Generation subculture.

But back to my course curriculum. What I felt was very much missing from the module option was an analysis of Beat writing as a movement of cultural appropriation.

For more rigorous academic work on this subject, this article from Douglas Field offers a great place to start.

As a long-time admirer of radical poetry that pushes the envelope, my knowledge of Amiri Baraka centred around his work in the Black Arts movement in the 1960-70s. To my surprise Baraka popped up again when I was trying to pinpoint writers of colour associated with the Beat Generation in the 1950s.

Going under his birth-name of LeRoi Jones (and I’m grateful that joining these dots introduced me to Hettie Jones - who is so much more than the title of her obituary suggests), Baraka was a New Yorker and befriended the Greenwich Village beats in the mid-1950s; all the while running and editing Yugen Magazine with Hettie - profiling pieces of poetry and work by the Beats.

Baraka (then Jones) wrote some work in the Beat style, namely, “Preface to a Twenty Volume Suicide Note” - and I’ve always found the following quote from Prof. William J. Harris to be very telling:

This book came out when I was in my late teens and helped me to find my direction as a young poet. Baraka was part of the same camp as I was: New American poetry, the world of Allen Ginsberg, Charles Olson, and Robert Creeley. At the time, I was much whiter, less interested in my black identity; I responded to the Beat Baraka, not the black one.6

Harris, in his review of (an excellent and comprehensive) Baraka poetry anthology draws attention to the “whiteness” of Beat poetry, aligning Beat as a form of “whiter” expression. Given the poetic scope and political growth Baraka went through in his lifetime, moving away from the whiteness of the Beats to radical, unapologetic Black writing, Black vernacular, Black breath - Harris reminds me of bell hooks when she talks about her first days at university where she felt she had to speak in a white-coded “Standard English” in order to be heard inside education institutions. hooks said:

When I first read these words, and now, they make me think of Standard English, of learning to speak against black vernacular, against the ruptured and broken speech of a dispossessed and displaced people. Standard English is not the speech of exile. It is the language of conquest and domination; in the United States, it is the mask which hides the loss of so many tongues, all those sounds of diverse, native communities we will never hear, the speech of the Gullah, Yiddish, and so many other unremembered tongues.7

For Baraka, I would contend that his early engagement with the Beats and seeing them appropriate Black writing, Black vernacular, Black breath was a breaking-point moment where he not only broke with his “whiter” identity Harris refers to, but also changing his name and centring his Blackness as the formative element of his lived experience.

Appropriating Black writing, Black vernacular, Black breath

But how did the Beats appropriate Black culture and lived experiences? Writing Blues People in 1963 undoubtedly saw Baraka make links between the organic grassroots jazz and rock and roll that emerged from African-American communities in the United States and the performances of the Beat poets in their New York coffeehouses.

Jack Kerouac’s style of writing, which he coined as “spontaneous prose” - so much so that he allegedly wrote On the Road on one full scroll of paper - contains repetitions, chaotic sentence structures, line breaks that all link back to jazz stylings and breaths. Taking their cue from jazz songs, Beats then heightened these narrative changes when performing - mimicking jazz and rock and roll aesthetics.

In On the Road, we see a more overt appropriation of Black lives and the experiences of marginalised people of colour in the United States. In a truly stunning moment in the novel, protagonist Sal Paradise reflects:

I walked … wishing I were a Negro, feeling that the best of the white world had offered was not enough ecstasy for me, not enough kicks, darkness and music…I wished I was a Denver Mexican or even a poor overworked J*p, a anything but what I was so drearily, a “white man”, disillusioned.8

In 1957 - a year when the first federal civil rights legislation to be passed since 1875 to begin to protect the enfranchisement of Black people was enacted; and when federal troops were sent into schools to uphold the court-ordered integration of pupils across the States - Kerouac published On the Road. Here he laments that the “white world” doesn’t hold enough “kicks, darkness and music” for his spoiled protagonist who, at any moment could be bailed out with a call to his aunt to send money.

Kerouac’s fetishisation of the lived experiences of marginalised folks - for example, Japanese Americans, many of whom suffered under internment in the post-WW2 years, and the working man - is an almost-perfect example of the insidiousness of white supremacy that pervades every aspect of society, culture and politics of the United States - at any time in its brief history as an “established” country.

And remember: Sal Paradise traverses the United States, across state borders, hitch-hiking in relative safety, without fear or threat.

Unfortunately, these examples of white ignorance in On the Road are not a one-off, and instead manifest into something much more sinister with the publication of Kerouac’s grotesque Pic (not linked on purpose). Pic (1971) details the story of Pictorial Review Jackson, a ten-year-old black boy, and his brother, Slim, who hitchhike from North Carolina to New York City. The core of this novel was written pre-On the Road in 1951, and was finished with scraps from The Town and the City (1950).

The whole novel is written in African-American dialect and below is a revolting example of the text:

Come nightfall ever’body go to bed, and I’se in the bed with my th’ee little bitty cousins and can’t sleep none, and say to myself, ‘Oh me, what happen to me next?’ and I’sewearisome for ever’thing and can’t neither cry nor nothing no more. Ever’thing I fixed on done run out on me and wasn’t nothin I could do. Lord, it was a bad long night.

OG Twitter folks might remember the uproar when Margaret Mitchell’s 1936 novel Gone with the Wind was tweeted out line by line, amplifying the derogatory and dehumanising dialect the white author Mitchell chose to write Black folks in.

On this issue, I felt the following observation from Prof. Jacqueline Stewart in 2020 was particularly instructive: “It is precisely because of the ongoing, painful patterns of racial injustice and disregard for Black lives that Gone with the Wind should stay in circulation and remain available for viewing, analysis and discussion. Gone with the Wind is a prime text for examining expressions of white supremacy in popular culture”.9

By comparison, discussion and analysis of Kerouac - and moreover the Beat Generation - with regards to racism has been, in my readings, extremely muted.

This translates into horror when I see bright-eyed young students coming in to class to read novels where through the author’s blasé rejection of whiteness, whiteness is luxuriated in; and where Kerouac goes even further by embodying a young Black boy in Pic and in a way inverting Black vernacular into the “language of conquest and domination” that hooks spoke of.

I am not arguing that these texts shouldn’t be taught. But if they are, the contexts must also be! And from my readings, Kerouac is most often applauded as a purveyor of life through the eyes of an “outsider observer” (to quote a recent review I won’t link) than an active participant in cultural appropriation.

I was recently drawn to an article in Sonder Magazine that offered some additional illumination to the argument that the Beat Generation are guilty of mass efforts of cultural appropriation. The article stated that the word “beat” actually comes from an old African-American term for being “truly hopeless and beat down as a result of suffering abhorrent social injustice”. The article mourned the appropriation of this term from “a black expressive cultural marker to a white person’s fashion trend.” When reading and teaching the Beat Generation to students, it is that poignant and rage-inducing quotation should be front and centre of the handbook.

There is a famous quote from the musician Brian Eno about the Velvet Underground - “the first Velvet Underground album only sold 10,000 copies, but everyone who bought it formed a band”. The same can be said about the Beat Generation writers. Their impact on culture and literature is still felt today. Levi’s Jeans made millions from them. The thrall of the open road and imageries of stars exploding in the skies still inspire and encourage youngsters to explore and experiment, simulating freedom with a mapped-out horizon.

Without question, the Beat Generation offered valuable and impactful words. And that’s what makes it all the more important and necessary to tell the whole story about the Beats - not just the white one.

**Please note, as a white European woman I take my lead and all direction on Black vernacular, culture and writings from Black critics, thinkers and folks. I am constantly learning, often wrong and grateful for the emotional and intellectual labour carried out by Black folks and people of colour to create these resources.**

Counter culture movements are concerned with challenging society and are primarily anti-mainstream. While many folks inspired by the Beats did become proponents of counter cultural movements, the Beat Generation itself wanted to ‘opt out’.

Jack Kerouac, ‘About the Beat Generation,’ in Ann Charters, ed., The Portable Jack Kerouac (New York: Viking Penguin, 1995): 559-562.

Of all those writers associated with the Beat Generation, I would argue the three east coast writers cited (Ginsberg, Ferlinghetti, Snyder) arguably grew the most and post-Beat, became warriors for social change and advocacy. Snyder’s Turtle Island in particular is cited as one of the most important works of eco-criticism in the 20thC American canon).

Anne Waldman, Foreword, Women of the Beat Generation by Brenda Knight, Berkeley: Conari Press, 1996: x.

bell hooks, Teaching to Transgress: Education as the Practice of Freedom. New York: Routledge, pp.167-175, 1994.

Kerouac, Jack. On the Road. London: Penguin Group, 2000, p. 180.

![On The Road – [FILMGRAB] On The Road – [FILMGRAB]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Febfd430a-d6a3-410a-b614-41e34c992124_1280x544.jpeg)

Love this, so brilliant x

When I saw the subject of this in my email, I first thought it was from Lithub and thought, "I must send that to Maeve." I'm glad you wrote this because I was recently telling someone about the photo and poem of "who took the picture of you three?" Of course I couldn't remember the details and tried to search handouts from our course and couldn't find it.